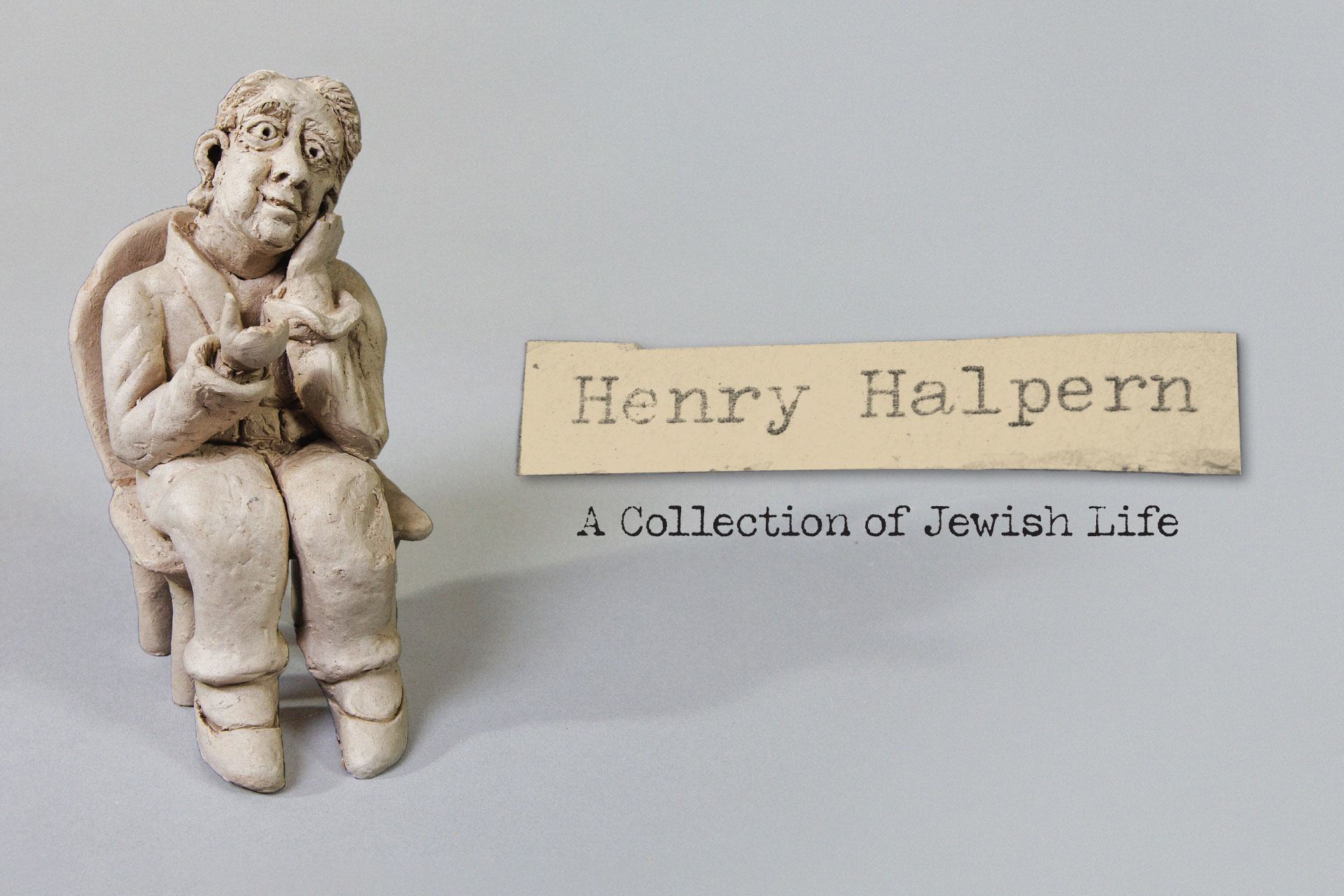

Henry Halpern: A Collection of Jewish Life

Learn about the conservation efforts taking place from the Cultural and Natural History Collections on a historical donation of folk-art sculptures from the Malgert Halpern and Irving Cohen family that depict Jewish life and culture in pre-World War II Ukraine and the United States.

April 21, 2023

The University of La Verne has received a donation of historical folk-art sculptures from the Malgert Halpern and Irving Cohen family that depict Jewish life and culture in pre-World War II Ukraine and the United States.

The pieces are being preserved through a years-long conservation process led by the Cultural and Natural History Collections (CNHC) and a select team of university staff and students.

The “Henry Halpern Collection of Jewish Life” was created by Henry Halpern, who was born in Ukraine and lived from 1895 to 1979. Many of the pieces depict Halpern’s memory of what Jewish life was like in Ukraine prior to the Holocaust, which led to the ultimate destruction of his community. Others resemble Jewish traditions he preserved while living in the United States.

Each piece is made of delicate greenware, or unfired clay, and some scenes express various depictions of Halpern’s small town or “shtetl.”

“They are expressive, very dynamic, they are very emotive,” said Anne Collier, former curator of the CNHC.

The university received 14 mostly intact scenes in early 2022. Each scene includes multiple pieces that tell rich stories from Halpern’s life. His family donated scores of additional sculptures over the following months, many depicting individual characters rather than complete scenes, bringing the number of pieces in the collection to more than 50.

The conservation of these pieces takes time and patience, since they are brittle and heavily aged. They’ve been moved to a climate-controlled space and have been carefully dusted of years of layered dirt and debris.

Once the sculptures are cleaned, reassembled, and stabilized, they will be displayed publicly and studied by students. Students will also be able to assist in the process of conservation, historical research, and curation, Collier said.

Collier enjoyed uncovering the history behind the sculptures and scenes.

“It’s the person behind the story, never the object,” Collier said. “There’s so much more to learn about these sculptures.”

Halpern grew up in a religious family in Ukraine and was enlisted in the Russian army during World War I, according to his family. He spent time in an Austrian prison camp and, upon his release, developed the skills to become a tailor. Later, he immigrated to the United States and opened stores that sold clothing and shoes.

Halpern, who was not formally trained as an artist, created most of the sculptures later in his life, after he retired to California, both to preserve his memories and provide a creative outlet for his energy, according to his family.

Robyn Small served as the Halpern and Cohen family’s caregiver for the sculptures and was introduced to the University of La Verne through her husband. After meeting President Devorah Lieberman and Chaplain Zandra Wagoner, Small felt the alignment between Halpern’s sculptures and the university’s values made the university “the perfect fit” to care for them.

“His gift in forming the clay people was his way of teaching what is important in any culture: working together; debating the meaning of faith; visiting the sick; lively exchanges at the market; simple vignettes of daily life,” Small said.

Wagoner agreed that the sculptures embody the university’s commitment to interfaith teaching, diversity and inclusivity, and lifelong learning.

“We are so thankful for the opportunity to preserve this history that so easily communicates through its visual representation,” Wagoner said.